Reign of terror: summary

Also known simply as 'The Terror', the Reign of Terror was incited by factors such as political and religious upheaval. During 'The Terror' anyone considered an enemy of the Revolution was executed. At this point, an enemy was essentially anyone suspected of opposing revolutionary ideas. The death toll ranged in the tens of thousands, with around 17,000 of those being official executions.

Causes of the Reign of Terror

The main cause of the Terror was the perceived disunity of France at a time of extreme political instability in the face of internal crisis and external threats. This instability showed itself in religious and popular rebellions as well as disagreements over the management of those threats.

Threats of foreign invasion

The monarchies of Europe were hostile to the French Revolution, fearing that revolutionary ideas would spread to their own dominions if it was not stopped. This led Leopold II of Austria (brother of Marie Antoinette) and Frederick William II of Prussia to issue the Pillnitz Declaration on 27 August 1791. The Declaration stated that they would invade France if the French King Louis XVI was threatened, and called on other European powers to join them.

The Declaration created a real fear of invasion and a sense that outside forces were meddling in French affairs. This not only made the revolutionaries more hostile to the King who was thought to be conspiring with other monarchs but led the Jacobins and Girondins to declare war against Austria and Prussia on 20 April 1792. This started the War of the First Coalition.

Jacobins: originally founded as the Club Breton, the Jacobin Club was led by Maximilien Robespierre from 31 March 1790. Jacobins were radicals concerned that the aristocracy and other counter-revolutionaries would do anything to reverse the gains of the Revolution.

Girondins: the Girondins were never a formal club but an informal alliance, centred around deputies from the southwestern Gironde region (of which Bourdeaux is still the capital). The Girondins supported the Revolution but opposed its increasing violence and favoured a decentralised, constitutional solution.

France suffered devastating defeats in the war until September 1792 when they stopped the Austro-Prussian forces from invading France at the Battle of Valmy.

Their prolonged defeats created paranoia around the continued threat of invasion. This served as a justification for the violence of the Terror, necessary to unify France in the face of foreign threats. Indeed, Louis Antoine de Saint-Just, the president of the National Convention, who would become known as the Archangel of the Terror, defended the use of violence:

That which produces the general good is always terrible, or it seems utterly strange when it is begun too early.

National Convention: a unicameral (one house only) parliament that governed France from August 1792 to October 1795.

The First Coalition consisted of the Austrian and Russian empires, the Dutch Republic, and the kingdoms of Prussia, Spain, Naples, Portugal, Sardinia, and Great Britain. These countries were committed to defeating France and undoing the Revolution.

The War of the First Coalition started when France declared war on Austria on 20 April 1792, following the Pillnitz Declaration, rapidly bringing Austria's ally, Prussia, into the war against France. Several other European states joined and formed the First Coalition. The war lasted more than five years, ending in 1797, and took place mainly along the eastern borders of France, with fighting in Flanders (now in Belgium), along the Rhine, and Italy.

The war saw the creation of French client states, the first 'sister republics': the Batavian Republic (the Netherlands) and the Cisalpine Republic (northern Italy). Several future French leaders got their start during this war, most notably a young Napoléon Bonaparte who helped retake the southern city of Toulon from an alliance of French royalists and Coalition forces in 1793.

Popular pressure

The need for Terror was increased by the constant pressure on the Convention from ultra-revolutionary groups. On 10 March 1793, the Revolutionary Tribunal was created in order to judge the actions of perceived enemies of the Revolution. The tribunal's creation was a response to several uprisings that sprung up all over France against the National Convention, known as the Federalist Revolts. Like the Girondins, Federalists favoured a decentralised France. Notable revolts took place in the Vendée and Lyon in 1793.

An uprising by a radical revolutionary sect known as the Enragés took place on the same day as the Tribunal's creation. The sect was known for extremist views and constantly instigated uprisings to force the Convention to take more radical revolutionary actions. In response, on 18 March 1793, the Convention issued the death penalty for anyone supporting the views of the Enragés.

A key turning point in the course of the Terror was an armed insurrection by the sans-culottes which took place between 31 May and 2 June 1793. The sans-culottes stormed the Convention and demanded that its 29 Girondin deputies be expelled because the sans-culottes viewed them as too moderate.

Sans-culottes: literally 'without breeches', this is a term used to describe working-class revolutionaries, so-called because they were stereotyped as wearing more practical trousers rather than knee-breeches. Originally an insult, it was adopted as a term of pride. The sans-culottes would be the backbone of the Revolution in its early years.

The Jacobins took this opportunity to arrest the Girondins and take over the Convention. As a result, increasingly terroristic methods were used to maintain the unity of the country.

Religious upheaval

The French Revolution was characterised by a dramatic rejection of religion. The conflict between those who rejected the concept of God entirely in favour of atheism and those who still remained devoted to Catholic Christianity created extreme religious upheaval all around France. This became another cause that urged the use of terror to maintain order.

The first tangible rejection of Catholicism came with the Civil Constitution of the Clergy, issued on 12 July 1790. This involved the reorganisation of the Catholic Church, effectively making priests into civil servants, with wages paid by the State, and a system of elections.

On 27 November 1790, the National Assembly commanded members of the clergy to take an oath proclaiming their support for the French constitution and reorganising the church. Only around 50% of French priests took the oath, splitting the French church. As historian Noelle Plack put it:

While on paper asking clerics to take an oath of fidelity to the nation, the law, the king, and the new Revolutionary constitution may have seemed relatively benign, in reality it became a referendum on whether one’s first loyalties were to Catholicism or to the Revolution.1

National Assembly: the National Constituent Assembly governed France following the Storming of the Bastille in July 1789 and dissolved itself in October 1791.

To maintain order, the National Convention tried various methods:

- It created the Law of Suspects in September 1793, arresting many dissenting priests.

- On 5 October 1793, the Convention decided to abolish all religious holidays and created a new non-religious calendar. The date of the First French Republic's establishment in 1792 became Year I.

- To replace Catholicism Maximilien Robespierre attempted to create a form of deism in the Cult of the Supreme Being. Robespierre thought atheism would encourage anarchy and that the populace needed a common faith, but his plan utterly failed. It only encouraged a further divide in the country as many people refused to follow the Cult and thus intensified the need for Terror.

Deism: belief in the existence of a supreme being/creator, who does not intervene in the universe.

Cult of the Supreme Being: a religion of 'reason' created by Robespierre based on Enlightenment values.

Events and purpose of the Reign of Terror

The Terror's purpose was to maintain the unity of France during a period when multiple internal and external actors were threatening the Revolution. So, what happened during the Terror?

The Committee of Public Safety

The Terror had its foundation in the Committee of Public Safety which was brought into being in April 1793. The National Convention supported the Committee's near-dictatorial power as they thought offering them expansive powers would lead to efficiency of government.

Committee of Public Safety: the provisional government of France between April 1793 and July 1794. Robespierre was elected to the Committee of Public Safety in July 1793 and used it to eliminate his enemies.

The Committee's main role was to protect the Republic against foreign attacks and internal division. It was given control over military, judicial, and legislative efforts but this was only to be a wartime measure.

The Committee struggled to control the populace, and as the threat of invasion by the First Coalition grew, along with internal strife, so did the Committee's powers. This was because the Committee believed that the more tightly they controlled the French people, the more unified the country would stay.

Maximilien Robespierre and the Reign of Terror

In July 1793, following the expulsion of the Girondists from the National Convention, the leaders of the Jacobin Club, Maximilien Robespierre and Saint-Just, were elected to the Committee.

The power of the Committee of Public Safety increased following this unrest, with the National Convention giving it executive powers. The Committee attempted to use these powers to persecute the Federalists, Girondins, monarchists, and others suspected of counter-revolutionary activity like the clergy. This caused a falling-out between Robespierre and his former ally and popular Jacobin leader, Georges Danton, who renounced the use of political violence.

The Committee’s increasingly extreme stance did nothing to curb counter-revolutionary sentiment around France. Many moderates believed that the Terror went against the ideals of justice and equality upon which the Revolution was founded. To make matters worse, popular unrest and violence continued in the regions of Lyon, Marseille and Toulon.

Portrait of Maximilien Robespierre, commons.wikimedia.org

Portrait of Maximilien Robespierre, commons.wikimedia.org

The Execution of Danton

Robespierre wanted to carry the Revolution with one single will, as he put it. As a result, he conducted a fratricidal (brother-against-brother) campaign against any fellow Jacobins he perceived as counter-revolutionary or a threat to his position.

At the end of March 1794, Georges Danton, a vocal critic of the Committee of Public Safety, was arrested on charges of financial corruption and conspiracy. Robespierre insisted that Danton was in the pay of a foreign power, likely Great Britain. Danton and Camille Desmoulins, another prominent Jacobin and Montagnard, were executed along with thirteen others on 5 April 1794. The death of Danton would come back to haunt Robespierre.

The Law of 22 Prairal

Robespierre's manic wish to purify the Republic led to tyranny and he essentially killed anyone who disagreed with him. Thousands were arrested, and, on 10 June 1794, the National Convention passed the Law of 22 Prairial Year II (the corresponding date on the French revolutionary calendar), which suspended the rights to a public trial and to legal assistance.

Juries could only acquit or sentence the accused to death. Subsequently, the rate of executions increased sharply and at least 1300 people were executed in June 1794 alone. Executions increased to such an extent after the Law of 22 Prairial that the month following its enactment became known as the Great Terror, only ending with July's Thermidorian Reaction.

The Battle of Fleurus

On 26 June 1794, a French army under General Jean-Baptiste Jourdan won the Battle of Fleurus (in the Austrian Netherlands) against the First Coalition, marking a turning point in France’s military fortunes. With the First Coalition now on the backfoot, this lowered the likelihood that France itself would be invaded. It undermined the necessity of strict wartime measures and the legitimacy of the Revolutionary Government, which had justified extreme measures as necessary to resist foreign powers. Jourdan himself had been temporarily dismissed by Robespierre in early 1794.

Jean-Baptiste Jourdan in 1792, Wikimedia Commons.

Jean-Baptiste Jourdan in 1792, Wikimedia Commons.

The Thermidorian Reaction

The Thermidorian Reaction on 27 July 1794 (9 Thermidor Year II in the revolutionary calendar) was a parliamentary revolt against Maximilien Robespierre, who had been the leader of the National Convention since June 1794.

As the paranoia of the Great Terror gripped France everyone was suspecting everyone of treason. Robespierre addressed the National Convention on 26 July 1794 suggesting that he was aware of a number of people who had committed treason but he would not name them. This caused a frenzy amongst the members of the Committee as they feared that any of them could be convicted and executed.

To prevent this, the next day the members of the National Convention shouted him down and decreed his arrest. Robespierre along with his supporters barricaded at the Hôtel de Ville (the centre of the Parisian civic government) but he was arrested on 28 July 1794. On the same day, he was executed, along with 21 of his closest associates.

Over the next few days, around 100 supporters of Robespierre were executed. Although the Reign of Terror was ending, the White Terror had just begun: moderates now started terrorising the Jacobins and other radicals.

Consequences of the Reign of Terror

The Reign of Terror had the opposite results to those intended. Arbitrary executions and lack of accountability created a sense of paranoia across France. Many became completely disillusioned with the Revolution and helped fuel the counter-revolution calling for a return to the monarchy. Eventually, even Robespierre's former allies turned against him during the Thermidorian Reaction as he himself turned against his fellow Jacobins and Montagnards.

Montagnards: named for the highest benches of the National Assembly (La Montagne: 'The Mountain'), this was a loosely-defined inner circle of Jacobins that gathered around Robespierre from 1792 onwards.

When Robespierre was arrested on 9 Thermidor, he was rendered momentarily speechless. At this, a fellow deputy reputedly cried out:

The blood of Danton chokes him! 2

Robespierre, shocked at this, simply remarked that if the execution of Danton had bothered the members of the National Convention so much, then they should have done something to save him.

The Reign of Terror and the resulting White Terror permanently damaged the position of the Jacobin Club. They never again held the power that they did between 1792 and 94 and their membership dropped massively following the executions of Robespierre and his supporters. On 12 November 1794, the National Convention unanimously passed a decree permanently closing the Jacobin Club.

The Reign of Terror - Key takeaways

The Reign of Terror (1793–94) was a period of violence during the French Revolution incited by several factors such as political and religious upheaval.

The main causes of the Terror were the perceived threats of the Revolution within and outside of France. Notable examples were the threat of invasion by foreign monarchies and pressure inflicted on the Convention by radical French sects.

The purpose of the Terror was to maintain French unity. The country was fracturing due to religious, social, and political pressures. The Convention thought that they could force everyone to comply with their vision of revolutionary government through terroristic methods.

The effects of the Terror were devastating to France. Many became utterly disillusioned with the Revolution and even called for a return to the monarchy. Ultimately, the Thermidorian reaction and the fall of Robespierre brought an end to the Terror and the beginning of the White Terror.

1. Noelle Plack, 'Challenges in the Countryside, 1790–2', in David Andress (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of the French Revolution (Oxford, 2015), p. 356.

3. Simon Schama, Citizens: A Chronicle of the French Revolution (New York, 1999), p. 844.

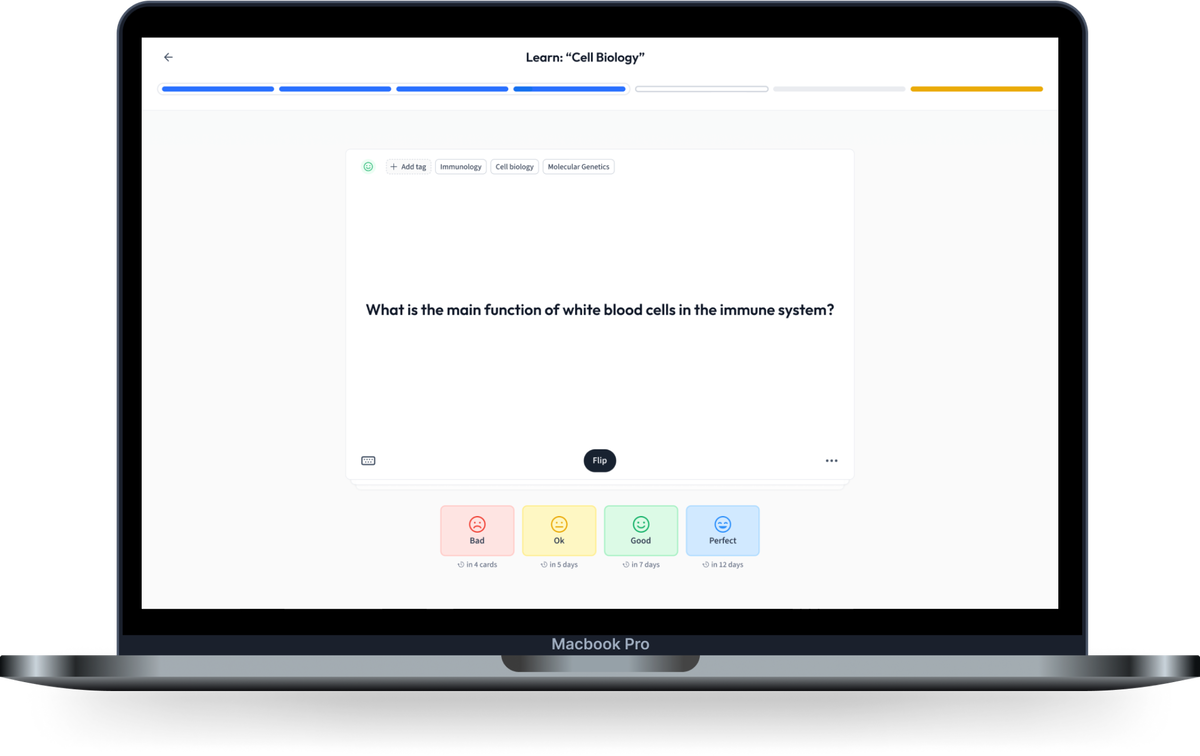

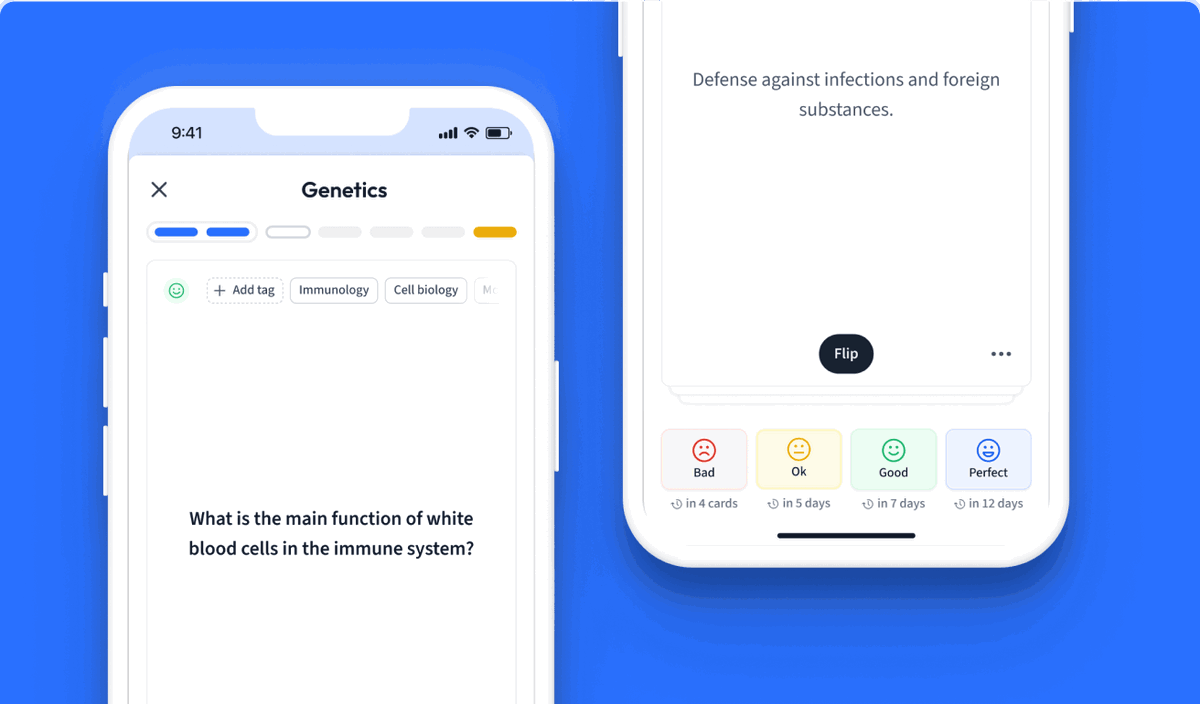

Learn with 71 The Reign of Terror flashcards in the free StudySmarter app

We have 14,000 flashcards about Dynamic Landscapes.

Already have an account? Log in

Frequently Asked Questions about The Reign of Terror

What happened during the Reign of Terror?

During the Reign of Terror, Maximilien Robespierre and the Girondins used the powers of the Committee of Public Safety to execute around 17,000 suspected 'counter-revolutionaries' and imprison many more. They justified these executions as necessary to unify France against the threat of the First Coalition. Ultimately, this failed and the National Assembly turned against Robespierre in the Thermidorian Reaction.

Why did the Reign of Terror end?

The Reign of Terror ended with the arrest and execution of Maximilien Robespierre on 28 July 1794. The execution of popular politician, Georges Danton, in April 1794 and the escalating violence of the period between June and July 1794 finally turned the National Convention against Robespierre and the Terror.

What was the Reign of Terror and why was it important?

The Reign of Terror was a period of nearly a year from September 1793 onwards, during which Maximilien Robespierre and the Girondins used the powers of the Committee of Public Safety to execute around 17,000 suspected 'counter-revolutionaries' and imprison many more. This was the most radical phase of the French Revolution and the instability and violence disillusioned many republicans. In 1795, it led to the royalist White Terror and the creation of the French Directory to restore order.

What is a summary of the Reign of Terror?

The Reign of Terror was a period of mass execution in France between 1793 and 1794, carried out by the Committee of Public Safety against anyone suspected of 'counter-revolutionary' ideas.

How did the Reign of Terror affect France?

The Reign of Terror increased unrest in France and turned the National Assembly against Robespierre and the Girondins, leading to Robespierre's downfall in the Thermidorian Reaction. The Reign of Terror also prompted a royalist reaction in the form of the White Terror and the increased unrest led to the formation of the French Directory.

About StudySmarter

StudySmarter is a globally recognized educational technology company, offering a holistic learning platform designed for students of all ages and educational levels. Our platform provides learning support for a wide range of subjects, including STEM, Social Sciences, and Languages and also helps students to successfully master various tests and exams worldwide, such as GCSE, A Level, SAT, ACT, Abitur, and more. We offer an extensive library of learning materials, including interactive flashcards, comprehensive textbook solutions, and detailed explanations. The cutting-edge technology and tools we provide help students create their own learning materials. StudySmarter’s content is not only expert-verified but also regularly updated to ensure accuracy and relevance.

Learn more