Commensalism definition in biology

Commensalism is a type of symbiotic relationship seen in nature. While the word commensal might remind us of the word community, the actual etymology of the word commensal indicates a more direct meaning in French and Latin. Commensal comes from the joining of two words: com- which means together, and mensa- which means table. Commensal more literally translates to “eating at the same table”, a beautiful turn of phrase.

In community ecology, however, commensalism is defined as a relationship in which one species benefits and the other does not benefit, but is also not harmed. Commensalism leads to benefits for one organism, and neutrality for the other one.

Symbiosis is a term encompassing the broad range of communal relationships that organisms and different species can have when living on, within, or near each other. If both species benefit, the symbiosis is termed mutualism. When one species benefits, but the other is harmed the symbiosis is termed parasitism. Commensalism is the third type of symbiotic relationship, and that is what we will examine further (Fig. 1).

Features of commensalism in relationships

What are some features we see time and again in commensalism and commensal relationships? Just like in parasitism, the organism that benefits (known as the commensal) tends to be significantly smaller than its host (the host is the organism that does not change or receives only neutral changes due to the symbiotic relationship). This makes sense because a very large organism might inevitably bother or harm the host if it was living on or around it. A smaller commensal can be more easily ignored than a bigger one would be.

Commensalism can vary in its timing and intensity, like any other symbiotic relationship. Some commensals have very long-term or even lifelong relationships with their hosts, while others have short-lived, transient relationships. Some commensals may derive extreme benefits from their hosts, while others may have weak, minor benefits.

Commensalism – the debate: is it even real?

Believe it or not, there is still a debate as to whether true commensalism actually exists. Some scientists believe that every symbiotic relationship is either mutualistic or parasitic and, if we think we are seeing commensalism, that is only because we have yet to discover how the host either benefits from or is harmed by the relationship.

This theory could be possible, especially when we take into account some of the weak, transient, or paltry examples of commensalism we have. Perhaps if we study all commensal relationships in depth, we will discover that they are indeed some other kind of symbiosis. However, for now, this theory is not commonly accepted. We believe commensalism exists, and there are several examples of commensalism that we have in nature.

Commensal organisms on a macro level

Commensalism is thought to have developed between larger species (not microbes) due to certain evolutionary changes and ecological realities. Larger species, such as humans, fed on things and created waste, and then other species may have learned to follow near to humans to consume their waste. This occurred without harming the humans.

In fact, one of the theories of how dogs were tamed and domesticated involves the principles of commensalism. As ancient dogs kept coming closer to humans to consume the leftovers of their meat, humans eventually developed bonds with first individual dogs and then whole communities of dogs. These dogs were naturally less aggressive than some other species of animals, so they took to these bonds with greater ease. Ultimately, social ties were established between dogs and humans, and this became one of the bedrocks of their ultimate domestication.

Commensal gut bacteria – the debate

Human beings have what is called a gut microbiota, which is a community of bacteria and microbes that live in our gut and control and modulate certain chemical processes there.

These processes include making Vitamin K, which is produced by certain intestinal bacteria, and increasing metabolic rate which helps reduce the likelihood for obesity and dyslipidemia.

Another very important function of our gut microbiome is to fend off other bacteria, especially pathogenic bacteria, that would like to latch on and cause gastrointestinal infections, with symptoms like nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. If our natural gut bacteria are present, colonizing our intestines, there is not as much room or opportunity for pathogenic bacteria to take hold.

Some people get sick with stomach bugs after taking antibiotics. This seeming paradox is because the antibiotics killed the “good” bacteria of their gut microbiome, giving room for pathogenic bacteria to take hold and cause infection.

Yet with all these important activities that our gut bacteria help us to regulate and maintain, there remains a debate as to the actual classification of the gut microbiome. Is our relationship with our gut bacteria an example of commensalism, or is it an example of mutualism?

Obviously, we as humans benefit tremendously from our gut microbiome, but do the bacteria benefit from this symbiosis as well? Or are they merely neutral, neither harmed nor helped by it? So far, most scientists have not outlined clear, specific benefits to bacteria that arise from them dwelling in our intestines, so our gut microbiome is more often considered an example of commensalism than mutualism. Still, some scientists think that microbes benefit from our moist, warm environment and the food products that we consume and digest. So the debate rages on.

Commensalism examples in biology

Let's look at some examples of commensalism, irrespective of the scale or size of the organisms and the length of time that the relationship occurs for.

Phoresy- with millipedes and birds

Phoresy is when an organism attaches to or stays on another organism for transport.

Commensal: millipede

Host: bird

Because birds are not bothered or harmed by the millipedes that use them as locomotive vehicles to go from place to place, this is an example of commensalism.

Inquilinism- with pitcher plants and mosquitoes

Inquilinism is when an organism houses itself permanently within another organism.

Commensal: the pitcher-plant mosquito.

Host: pitcher plant

The mosquito uses the beautiful yet carnivorous pitcher plant as a home and from time to time, can also dine on the prey that the pitcher plant traps. The pitcher plant is not bothered by this. Both species have co-evolved to suit each other.

Metabiosis- with maggots and decomposing animals

Metabiosis is when one organism is dependent on the activity and/or presence of a different organism to create the environment that is required or most suitable for it to live in.

Commensal: Maggots

Host: dead, decaying animals

Maggot larvae need to live and grow on decomposing animals so that they can have the nutrients they need and reach proper maturity. The dead animal is already dead and thus isn't helped or harmed by the presence of the maggots, as gross as they are to us!

Monarch butterflies and milkweed plants

Commensal: monarch butterfly

Host: milkweed

Monarchs lay their larva on milkweed plants, which produce a particular toxin. This toxin is not harmful to the monarch larvae, which gather and store some of the toxin within themselves. With this toxin within them, monarch larvae and butterflies are less appetizing to birds, who would otherwise want to eat them. The monarch larvae are not harmful to the milkweed plant, because they do not eat it or destroy it. The monarchs do not add any benefit to the milkweeds' lives, so this relationship is one of commensalism.

Golden jackals and tigers

Commensal: golden jackal

Host: tiger

Golden jackals, at a certain stage of maturity, may be expelled from their pack and find themselves alone. These jackals may then act as scavengers, trailing behind tigers and eating the remains of their kills. Because the jackals usually remain a safe distance behind and wait for the tigers to finish eating, they are not harming or affecting the tiger in any way.

Cattle egrets and cows

Commensal: cattle egret

Host: cow

Cows graze for long periods of time, stirring up creatures like insects that lie underneath the foliage. Cattle egrets perch on the backs of grazing cows and can snap up juicy insects and other things that the cows unearth (Fig. 2). Egrets are relatively light and don't compete for the same food as the cattle, so the cows are neither harmed nor better off due to their presence.

Commensalism – Key takeaways

- Commensalism is defined as a relationship between two organisms in which one benefits and the other receives neither harm nor benefit.

- Commensals occur in microbiology and on a more macro-level, between different animals and plants

- Our symbiotic relationship with our gut bacteria is typically considered commensalism.

- Animals can have commensal relationships with each other – such as jackals and tigers, and egrets and cows.

- Plants and insects can also be part of commensal relationships – such as monarch butterflies and milkweed plants.

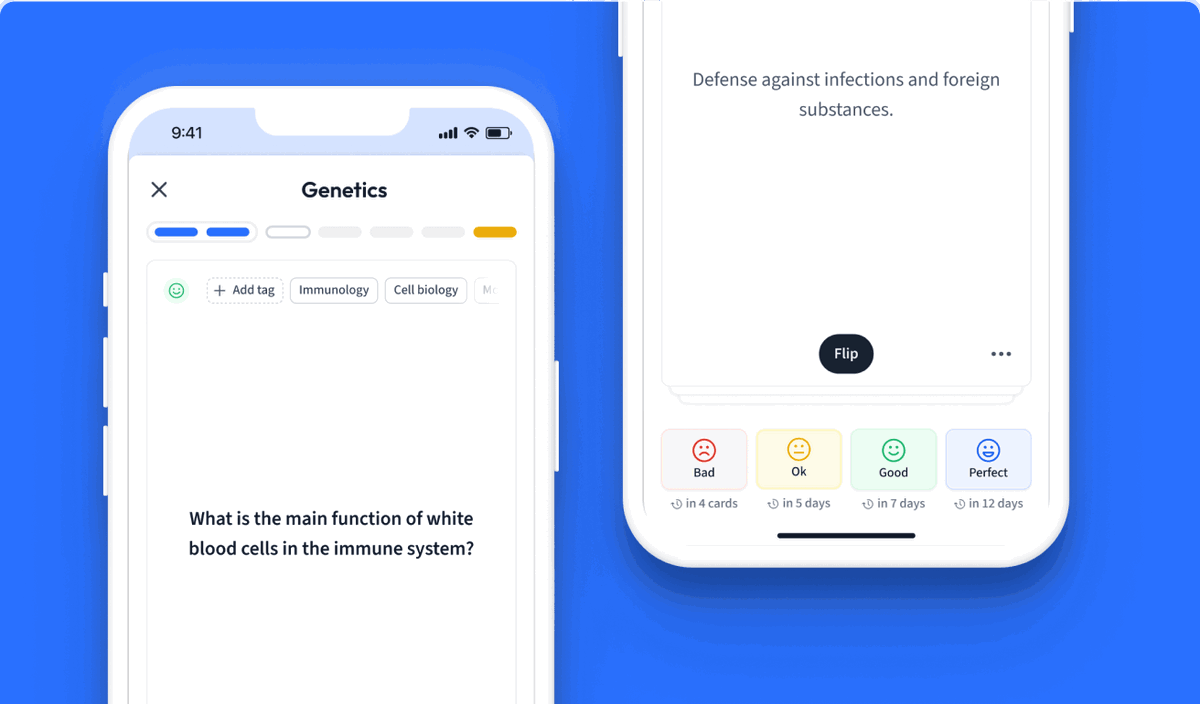

Learn with 14 Commensalism flashcards in the free StudySmarter app

We have 14,000 flashcards about Dynamic Landscapes.

Already have an account? Log in

Frequently Asked Questions about Commensalism

What is commensalism?

A symbiotic relationship where one organism benefits and the other in unaffected

What is an example of commensalism?

Cows and egrets - the birds that perch on them and eat insects the cows unearth while foraging for grass.

What is the difference between commensalism and mutualism?

In commensalism, one species benefits and the other is unaffected. In mutualism, both species benefit.

What is a commensalism relationship?

A type of relationship that exists between organisms where one of them benefits and the other is neutral (no benefit or harm)

What are commensal bacteria?

Gut bacteria of our intestinal microbiome that help us to digest food, make vitamins, reduce risk of obesity and protect against pathogenic infections.

About StudySmarter

StudySmarter is a globally recognized educational technology company, offering a holistic learning platform designed for students of all ages and educational levels. Our platform provides learning support for a wide range of subjects, including STEM, Social Sciences, and Languages and also helps students to successfully master various tests and exams worldwide, such as GCSE, A Level, SAT, ACT, Abitur, and more. We offer an extensive library of learning materials, including interactive flashcards, comprehensive textbook solutions, and detailed explanations. The cutting-edge technology and tools we provide help students create their own learning materials. StudySmarter’s content is not only expert-verified but also regularly updated to ensure accuracy and relevance.

Learn more