However, alcohol is more than just a guilty pleasure you might enjoy on a night out. Alcohols are actually important organic compounds. They're useful stepping stones in synthesis pathways and have many applications, from solvents to fuels. Glucose, the sugar used in respiration and the body's primary source of energy, is an alcohol. In this article, we're going to take a chemistry-based dive into the wonderful world of these organic compounds: alcohols.

- We will be delving into the chemistry of alcohols.

- We'll start by defining alcohol before looking at the different types of alcohols.

- Next, we'll explore alcohol nomenclature. You will be able to practice naming different alcohols.

- We'll then consider their properties, such as melting and boiling points and solubility.

- After that, we'll look at both producing alcohols and reactions of alcohols.

- Finally, we'll take a deep dive into alcohol units and the effect of alcohol on the body.

Alcohol definition

Alcohols are organic compounds containing one or more hydroxyl groups, -OH.

Here's ethanol. It is by far the most common and best-known alcohol.

Ethanol. StudySmarter Originals

Ethanol. StudySmarter Originals

Notice the oxygen and hydrogen atoms on the right? They form a hydroxyl group, and we represent it with the letters -OH. All molecules with a hydroxyl group are alcohols.

The hydroxyl group

Let's take a closer look at the hydroxyl group, -OH. There are a couple of things to note.

- Firstly, the group is polar. This is because oxygen is more electronegative than hydrogen and attracts the bonded pair of electrons towards itself. This makes oxygen partially negatively charged, and hydrogen partially positively charged.

- Secondly, oxygen has two lone pairs of electrons. These squash the C-O and O-H bonds together. It results in a bond angle of 104.5°, making alcohols v-shaped molecules.

The polarity and bond angle of the hydroxyl group.StudySmarter Originals

The polarity and bond angle of the hydroxyl group.StudySmarter Originals

For more on electronegativity, polarity, and how lone pairs of electrons affect the shape of molecules, check out Electronegativity, Polarity and Shapes of Molecules.

Alcohol general formula

Because alcohols share a functional group, they form their own homologous series - a family of compounds with similar chemical properties that can be represented by a general formula.

A general formula is a formula showing the basic ratio of atoms of each element in a compound, that can be applied to a whole homologous series.

Check out Organic Compounds, where you'll learn about the other features of a homologous series.

Alcohols with just one hydroxyl group all have the general formula CnH2n+1OH. This is handy, because it means that once we know the number of carbon atoms in an alcohol, we can work out its number of hydrogen atoms. An alcohol with n carbon atoms has 2n+1 hydrogen atoms, plus an extra -OH group. For example, an alcohol with 3 carbon atoms has hydrogen atoms, plus an extra one from the -OH group. In total, it has 3 carbon atoms, 1 oxygen atom, and 8 hydrogen atoms.

Why don't we show the general formula as CnH2n+2O? Well, separating the -OH hydroxyl group out helps show that the members of this group of compounds are all alcohols, as opposed to any other type of organic molecule.

Types of alcohol

Alcohols can be classified into three types in chemistry: primary, secondary, or tertiary. An alcohol's classification all to do with the molecule's alpha carbon.

The alpha carbon is the carbon atom directly bonded to the hydroxyl group.

To be more precise, classification involves how many R groups the alpha carbon is attached to, where an R group is a shorthand representation for any other hydrocarbon chain.

Here's how primary, secondary, and tertiary alcohols differ.

- In primary alcohols, the alpha carbon is bonded to zero or one R groups. This means that the alpha carbon, and therefore the hydroxyl group, is always found at the end of the molecule. We show that alcohols are primary alcohols with the symbol 1°.

- In secondary alcohols, the alpha carbon is bonded to two R groups. These can be exactly the same as each other or completely different - it doesn't matter. We show them with the symbol 2°.

- In tertiary alcohols, the alpha carbon is bonded to three R groups. Once again, these can be alike or totally different. We show tertiary alcohols with the symbol 3°.

Primary, secondary, and tertiary alcohols. Note the number of R groups attached to the alpha carbon atom in the different alcohol classifications.StudySmarter Originals

Primary, secondary, and tertiary alcohols. Note the number of R groups attached to the alpha carbon atom in the different alcohol classifications.StudySmarter Originals

Wondering how we name alcohols? We'll look at that next.

Nomenclature of alcohols

Naming alcohols is pretty simple. We follow all of the usual IUPAC nomenclature rules. Note the following:

- We use a root name to show the length of the molecule's parent chain.

- We use a suffix to show the molecule's highest priority functional group, known as its parent functional group. If the highest priority functional group is the hydroxyl group, we use the suffix -ol. However, if there are higher priority functional groups present, we instead show that the molecule is an alcohol using the prefix hydroxy-.

- We use numbers, called locants, to indicate the position of the hydroxyl group on the carbon chain. Locants also show the position of any substituents or other functional groups present. You can number the carbon chain from either direction, but remember that you firstly want the parent function group to have the lowest possible locant. If both numbering possibilities give the same number locant, you then want to locants of any other substituents or prefixes to add up to the lowest total possible.

- If there are multiple of the same functional group or substituent present, we use quantifiers such as -di- or -tri-.

Stuck with naming compounds? IUPAC Nomenclature has you covered.

Let's look at an example. Have a go at naming the alcohol below.

Name the following alcohol and give its classification.

An unknown alcohol to be named.StudySmarter Originals

An unknown alcohol to be named.StudySmarter Originals

Its longest carbon chain is four carbon atoms long, giving it the root name -but-. It has a hydroxyl group and a chlorine atom, meaning that the hydroxyl group is the parent functional group. As a result, we need the suffix -ol and the prefix chloro-. Numbering the carbons from the left, the hydroxyl group is found on carbon 2 and the chlorine group is found on carbon 4. Numbering from the right, the hydroxyl group is found on carbon 3 and the chlorine group is found on carbon 1. The first numbering possibility means that the parent functional group has the lowest possible locant, and so in this case, we number the parent chain's carbon atoms from the left. Putting that all together, we get 4-chlorobutan-2-ol.

Our unknown alcohol, with its functional groups and parent chain labelled, is known as 4-chlorobutan-2-ol.StudySmarter Originals

Our unknown alcohol, with its functional groups and parent chain labelled, is known as 4-chlorobutan-2-ol.StudySmarter Originals

In terms of its classification, the alpha carbon atom is bonded to two R groups. This is therefore a secondary alcohol. We've shown its alpha carbon and R groups down below.

The classification of our unknown alcohol. The alpha carbon is bonded to two R groups, making it a secondary alcohol.StudySmarter Originals

The classification of our unknown alcohol. The alpha carbon is bonded to two R groups, making it a secondary alcohol.StudySmarter Originals

Properties of alcohols

The properties of alcohols are greatly influenced by the polar hydroxyl group. We touched on this earlier, but let's go over it again now.

The hydroxyl group. StudySmarter Originals

The hydroxyl group. StudySmarter Originals

As we discovered, the hydroxyl group is polar. This is because oxygen is a lot more electronegative than hydrogen. The oxygen atom pulls the bonded pair of electrons it shares with hydrogen over towards itself, leaving hydrogen with a partial positive charge. Because hydrogen is such a small atom, it has a high charge density. Hydrogen's charge density is so high, in fact, that it is attracted to the lone pairs of electrons on the oxygen atom of an adjacent alcohol molecule. We call this hydrogen bonding. It is a type of intermolecular force that is much stronger than other intermolecular forces (such as van der Waals forces and permanent dipole-dipole forces).

Hydrogen bonding between adjacent hydroxyl groups. StudySmarter Originals

Hydrogen bonding between adjacent hydroxyl groups. StudySmarter Originals

You can read more about hydrogen bonding in Intermolecular Forces.

Now we'll explore how hydrogen bonding affects the properties of alcohols.

Melting and boiling points

Alcohols have high melting and boiling points compared to similar alkanes. This is because the hydrogen bonding holding adjacent alcohol molecules together is strong and requires a lot of energy to overcome. In contrast, alkanes are only held together by van der Waals forces. These are a lot weaker than hydrogen bonds and much easier to overcome. This gives alkanes low melting and boiling points.

As with all organic molecules, alcohols follow trends in melting and boiling points:

- As chain length increases, melting and boiling points increase. This is because the molecules experience stronger van der Waals forces.

- As branching increases, melting and boiling points decrease. This is because the molecules can't fit as closely together and so experience weaker van der Waals forces.

Solubility

Short-chain alcohols are soluble in water, whilst long-chain alcohols are insoluble. This is because the alcohol's polar hydroxyl group can also hydrogen bond with water molecules, dissolving the alcohol. However, in long-chain alcohols, the nonpolar hydrocarbon chain gets in the way of the hydrogen bonding and prevents the alcohol from dissolving.

Acidity

Alcohols are slightly acidic. According to the Brønsted-Lowry theory of acids and bases, all molecules which donate protons (H+) are acids. The hydroxyl group of alcohols tends to release H+ because of its polarity. Due to oxygen being more electronegative than hydrogen, the shared pair of electrons shifts towards oxygen, making the -OH bond weaker and easier to break. The release of H+ makes alcohol acidic.

Check out Brønstead-Lowry Acids and Bases for further information about acids and bases.

Producing alcohols

We mentioned that alcohols are important stepping stones in synthesis pathways. You can use them to make lots of other organic compounds. But how do we make alcohols themselves?

There are a few different ways. You might already be familiar with some of them, while some will be new.

Synthetic methods of alcohol production

In organic chemistry, it is often helpful to draw big synthesis mind maps that link different organic compounds, showing how you might get from one to the other and what conditions or catalysts you need. We'd highly recommend you make one if you haven't already, and gradually add to it as you learn more and more organic reactions. With such a map, it is easy to see all the different ways of producing a type of organic molecule; alcohols are no exception. Here are some examples of reactions that produce alcohols.

- Hydrating alkenes using steam and a phosphoric acid catalyst. For example, hydrating ethene gives ethanol.

- Reacting halogenoalkanes with the hydroxide ion in a mixture of alcohol and water. For example, mixing bromoethane with potassium hydroxide gives ethanol and potassium bromide. This is an example of a nucleophilic substitution reaction.

- Hydrolysing esters using water and a strong acid catalyst. For example, hydrolysing methyl ethanoate gives methanol and ethanoic acid.

- Reducing carboxylic acids, aldehydes, or ketones using a reducing agent such as LiAlH4 or NaBH4. Note that you can reduce aldehydes or ketones using both of these reducing agents, but you can only reduce carboxylic acids using LiAlH4. For example, reducing propanal produces propanol.

Let's now summarise the reagents, products, and conditons for the chemical reactions by which alcohols can be produced:

| Reactions that Produce Alcohol | ||

|---|---|---|

| Reaction | Reagents and Conditions | Products |

| Electrophilic addition of steam to alkene | H2O(g) and H3PO4 as catalyst | Alcohol |

| Oxidation of alkenes with cold dilute acidified potassium manganate (VII) | KMnO4/H+ | Diol + MnO2 (dark brown ppt) |

| Nucleophilic substitution of a halogenoalkane | NaOH and heat | Alcohol + sodium salt |

| Reduction of an aldehyde or ketone | NaBH4 or LiAlH4 | Alcohol + Al3+ |

| Reduction of a carboxylic acid | LiAlH4 | Alcohol + Al3+ |

| Hydrolysis of an ester | dilute acid or dilute alkali and heat | Alcohol + carboxylic acid / carboxylate salt |

Here's a quick version of a synthesis map, showing how you can make alcohols from other organic compounds.

A synthesis map centred on alcohols. StudySmarter Originals

A synthesis map centred on alcohols. StudySmarter Originals

Natural methods of alcohol production

The most common way of making alcohol for industrial purposes is through the hydration of ethene. But if we want to make alcohol for drinks such as wine, beer, or cider, we use a different process: fermentation.

Fermentation involves supplying tiny little yeast cells with plant carbohydrates such as sugar cane or sugar beet. The yeast breaks down the plant matter, converting it into ethanol. Fermentation takes place in anaerobic conditions at around 35°C.

Fermentation is a much slower process than the hydration of ethene, but it is a much more sustainable option. Ethene comes from crude oil, a non-renewable resource, and the processing and burning of crude oil releases carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. On the other hand, fermentation uses renewable plant matter. Overall, it is carbon neutral - any carbon dioxide released is offset by carbon taken in when the plants are growing.

Because of this, scientists are increasingly looking towards fermentation as a source of organic molecules for industrial processes. Once we get ethanol, we can then convert it into other organic compounds, using reactions like the ones you've plotted out on your synthesis map. For example, ethanol can be dehydrated into ethene, which can then be polymerised into polymers such as poly(ethene). Sustainable plastic, anyone?

Feel like you need more information? In Reactions of Alkenes, we go over making alcohols in hydration reactions, and in Production of Ethanol, you can directly compare ethene hydration with fermentation. In Nucleophilic Substitution Reactions, you'll find the mechanism behind producing alcohols from halogenoalkanes, while in Reactions of Esters and Reactions of Aldehydes and Ketones, you'll see ways of making alcohols from aldehydes, ketones, and esters.

Reactions of alcohols

Alcohols are fairly reactive, thanks to their polar hydroxyl group. They also make great fuels. in this next section, we're going to look at some of the other reactions involving alcohols.

- Alcohols combust in oxygen to produce carbon dioxide and water.

- They can be oxidised by an oxidising agent such as acidified potassium dichromate into aldehydes, ketones, and carboxylic acids. For example, oxidising ethanol produces ethanal, which can be further oxidised into ethanoic acid.

- They can be dehydrated using a strong acid catalyst to produce alkenes. For example, dehydrating propan-1-ol produces propene. This is a type of elimination reaction.

- They react in halogenation reactions to produce a halogenoalkane and water. These reactions take place under varying conditions, depending on the type of alcohol and the halogen used, and are examples of nucleophilic substitution reactions. For example, treating ethanol with sodium bromide and concentrated sulphuric acid produces bromoethane, water, and sodium sulphate.

- They react with carboxylic acids to form an ester in an example of a condensation reaction. For example, heating methanol and ethanoic acid with a strong acid catalyst produces methyl ethanoate and water. This is also known as esterification.

A synthesis map centred on alcohols.StudySmarter Originals

A synthesis map centred on alcohols.StudySmarter Originals

We can use an oxidation reaction to test for some alcohols. Mixing a primary or secondary alcohol with orange acidified potassium dichromate causes the potassium dichromate to turn green. But watch out - this test doesn't work for tertiary alcohols, and it will also give a positive result with aldehydes.

You could instead test for alcohols using solid phosphorous pentachloride, PCl5. If an alcohol is present, the reaction will produce white steamy fumes of hydrogen chloride which turn damp litmus paper red. However, this test also gives positive results with water and carboxylic acids. Your best bet is to use a combination of the two tests.

An alcohol of the formula CH3CH(OH)-R can be tested for the CH3CH(OH)- group by its reaction with alkali iodine, I2. This results in the formation of triidomethane, CHI3 (also known as iodoform), which is a yellow precipitate. The reaction goes like this:

- Iodine is added to the alcohol, with a little NaOH solution. NaOH reacts with I2 to form NaOI, which oxidises the alcohol to form an ester (or an aldehyde, if the "R" group is hydrogen). NaOH also removes any colour of iodine, which prevents a false positive test.

- In the next step, the hydrogens in the CH3- group are substituted by reaction with I2 in the presence of OH- ions.

- In the final step, the breaking of C-C bonds takes place in the presence of OH- ions. CHI3 is produced along with an ion RCO2-.

Identification of CH3CH(OH)- group in alcohols by reaction with iodine | StudySmarter Originals

If the yellow precipitate of triiodomethane is formed, the test is positive and confirms the presence of the CH3CH(OH)- group in the initial alcohol. Besides being a yellow precipitate, triiodomethane, also has a faint "medical" smell due to its use as an antiseptic.

You'll find out more about all of the various reactions mentioned above in Reaction of Alcohols.

Examples of alcohols including isopropyl alcohol

Finally, let's explore a few further examples of alcohols. Here are some other common alcohols and their uses.

- Methanol, CH3OH, is a precursor to methanal. This compound is also known as formaldehyde and is used to make paints, cosmetics, and even explosives!

- Ethanol, C2H5OH, is well-known for its use in alcoholic drinks but is also a great solvent. You'll find it in cosmetics and cleaning products.

- Ethanol is also used to bulk up fuels. For example, 'gasohol' is an ethanol-petrol mixture containing between 10 and 20 percent ethanol. The ethanol used always comes from fermentation, which makes gasohol a sustainable way to supplement our fuels whilst reducing carbon dioxide emissions.

- Bottles of rubbing alcohol, a powerful disinfectant used for sterilising and cleaning, contains mostly isopropyl, C3H7OH. This has the IUPAC name of propan-2-ol. Isopropyl is also used as a detergent, solvent, and anti-freeze.

What are alcohol units?

To measure the alcohol content of drinks, we use the term units. One unit is equal to 8g of pure alcohol. This is approximately the amount of alcohol that an adult human can get rid of in one hour and is theoretically a way to track your drinking. Current UK guidelines recommend keeping your alcohol intake to below 14 units a week and to spread your drinking out over several days.

Alcohol is partially toxic to humans. It acts as a suppressor of the central nervous system, slowing down your reaction time and impairing your ability to think straight. It also interferes with hormone production, leading to increased levels of feel-good hormones such as dopamine. This is why alcohol is loved by so many and plays such a major role in our lives.

Alcohols - Key takeaways

- Alcohols are organic compounds containing one or more hydroxyl groups, -OH.

- They have the general formula CnH2n+1OH.

- The hydroxyl group has a bond angle of 104.5° and is a polar group. Because of this, alcohols can form hydrogen bonds.

- Alcohols can be primary, secondary, or tertiary.

- We name alcohols using the suffix -ol or the prefix hydroxy-.

- Alcohols have relatively high melting and boiling points. Short-chain alcohols are soluble in water.

- Alcohols are most commonly produced by hydrating ethene or in fermentation.

- Alcohols take part in many other reactions and are important stepping stones in synthesis pathways.

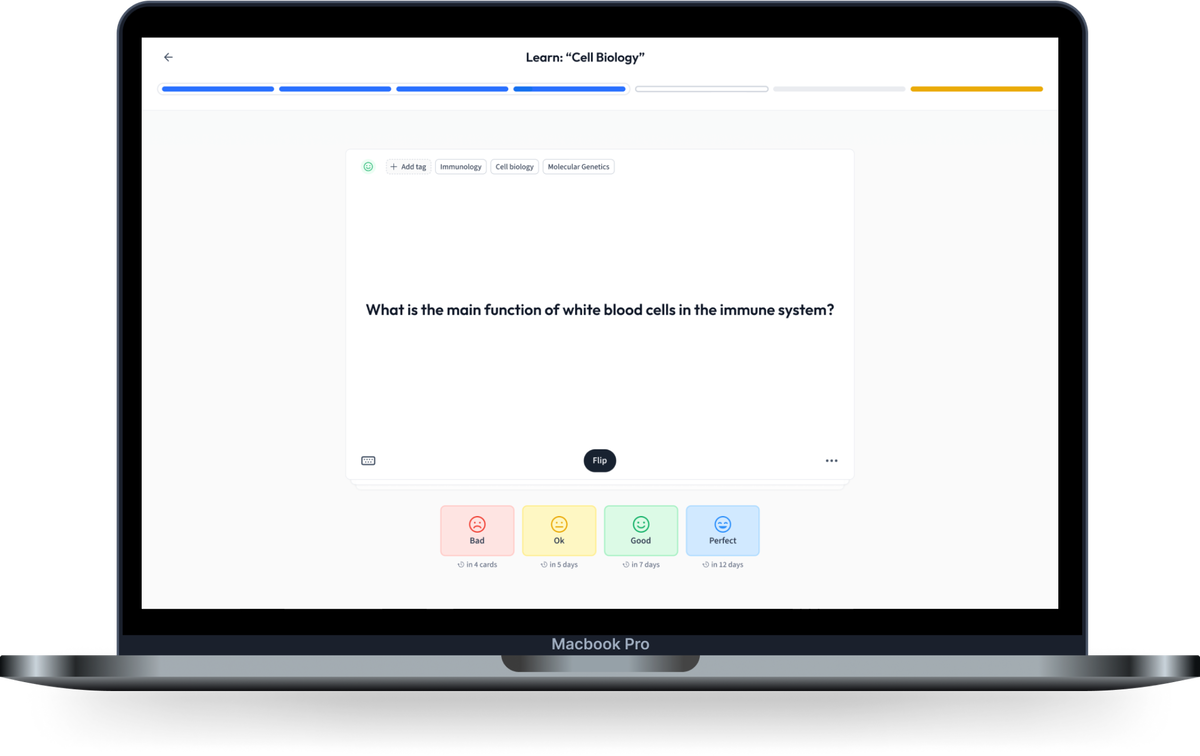

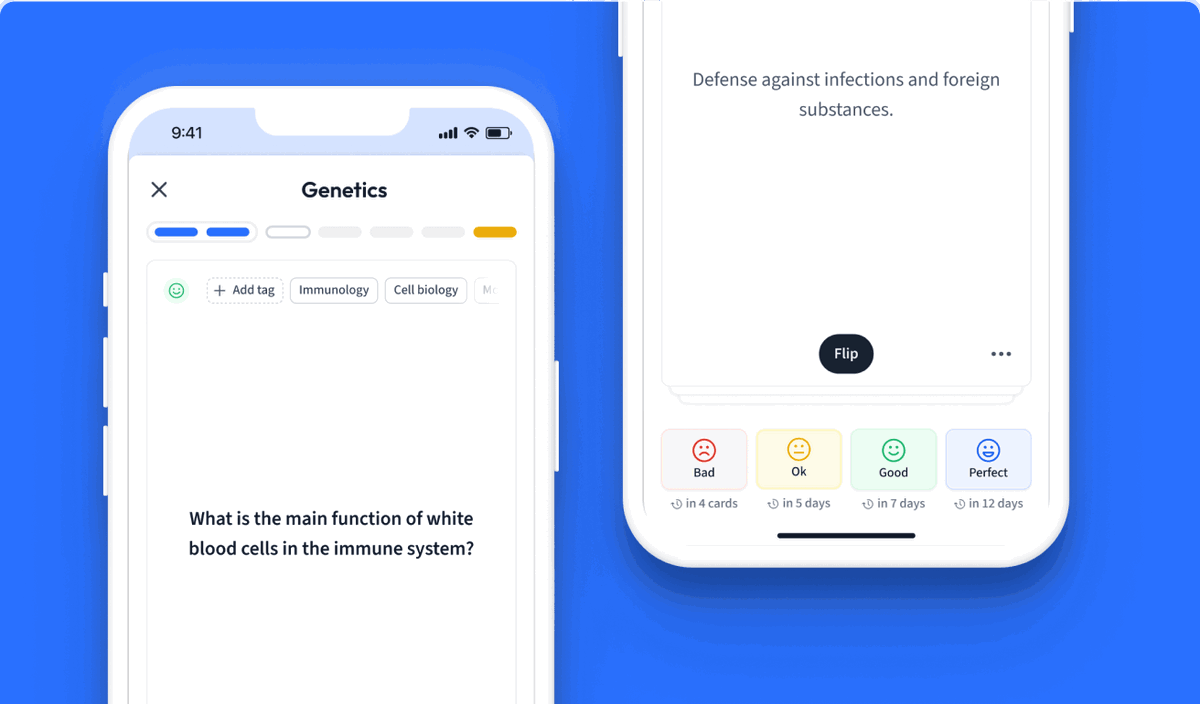

Learn with 19 Alcohols flashcards in the free StudySmarter app

We have 14,000 flashcards about Dynamic Landscapes.

Already have an account? Log in

Frequently Asked Questions about Alcohols

What is alcohol?

Alcohols are organic compounds containing one or more hydroxyl group, -OH.

What are examples of alcohols?

Examples of alcohol include methanol, ethanol and isopropyl, correctly named propan-2-ol.

What are the types of alcohol?

Alcohols can be split into three different types: primary, secondary, and tertiary. Their classification depends on the number of R groups bonded to the alpha carbon. Primary alcohols have zero or one R groups bonded to the alpha carbon, whilst secondary have two, and tertiary have three.

What are the uses of alcohols?

We find most alcohol in our everyday lives in the form of ethanol in alcoholic beverages. But alcohol is also used as a solvent, in fuels, and as a disinfectant.

How do you make alcohols?

Industrially, alcohols are made by hydrating ethene or fermenting biomass using yeast.

About StudySmarter

StudySmarter is a globally recognized educational technology company, offering a holistic learning platform designed for students of all ages and educational levels. Our platform provides learning support for a wide range of subjects, including STEM, Social Sciences, and Languages and also helps students to successfully master various tests and exams worldwide, such as GCSE, A Level, SAT, ACT, Abitur, and more. We offer an extensive library of learning materials, including interactive flashcards, comprehensive textbook solutions, and detailed explanations. The cutting-edge technology and tools we provide help students create their own learning materials. StudySmarter’s content is not only expert-verified but also regularly updated to ensure accuracy and relevance.

Learn more